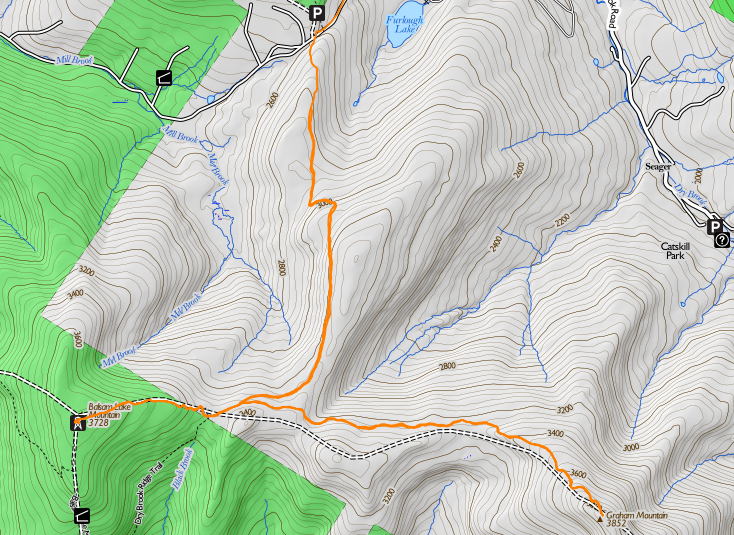

We started up from the DEC parking area on Mill Brook Road. This parking is nearly unique in the Catskills: first, you can drive right up to it on pavement, and second, it's at an elevation of 2,600 feet, so the ascents to the two mountains are only about 1,128 and 1,275 feet respectively. The trails are also unusual in the Catskills in that they involve no rock climbing. We didn't need to put hands to the rock, even for balance, all day.

The trail in to Balsam Lake Mountain runs over an estate that once belonged to rail baron Jay Gould, and still in the hands of his descendants. The state has a permanent easement for the trail to the fire tower (dating back to when the tower was staffed), and the family is also magnanimous about granting permission to hikers to cross their land. I had earlier telephoned the caretaker of the estate and got permission to climb Graham Mountain just for the asking. All that he asked in return was that Catherine and I carry out our trash and recognize that the family was not liable in any way for anything that happened to us on trail. I replied, "I understand that I'm a tolerated trespasser, not a welcomed guest, and will behave accordingly." (Somehow, I don't think the people who ask for permission are the ones that the Goulds need worry about!)

On the way up, we ran into a fair number of Tiger Swallowtail butterflies (Papilio glaucus). Of course, we took the usual excessive amount of time trying to photograph them. One individual had a behaviour that I hadn't seen before. On this windy day, when it alit on a flower, it used its hindwings to grasp the stem, giving rise to a photograph that looks as if the flower is passing right through the butterfly, and showing the unusual sight of the ventral wings displayed.

In this species, the dorsal and ventral sides look pretty much alike. There are diffferences, but they're subtle.

The trail makes an extremely gradual ascent over switchbacks to about the 3200-foot level, and then follows a contour line (which is a former road, named Old Tappan Road) to the DEC gate and public land. A side trail then branches off to the right and climbs 600 feet in five big steps to the fire observer's cabin, with the fire tower beyond.

As on most summer weekends, there was a caretaker at the summit. I passed some time in congenial conversation with him: he's a fellow electrical engineer and Long Islander. He also had a very nice Australian Shepherd dog - a well-trained trail dog - who got a bit of my salami as a treat and is now my friend for life. He lent us a pair of binoculars, and we mounted the stairs to the cab of the tower, which is a standard Aermotor steel model - the iconic American fire tower.

I happened to note at the site that there are bolts in several of the rocks. I suspect that whatever preceded the Aermotor tower, or some other facility at the summit, required guy wires. The Aermotor towers are free standing.

The tower enjoys a spectacular 360-degree view. Using the binoculars, Catherine was able to spot the Lackawaxen mines in far-off Pennsylvania and the obelisk at High Point in New Jersey.

For the closer views, we were much helped by the plotting board attached to the Osborne alidade in the center of the tower. By aiming its sights on a peak or lake, we could see on the map where we were looking.

We squeezed around each other in the cramped quarters of the 7x7-foot cab, and I managed to get a few decent pictures of the views. To the north, the Blackheads and the Devil's Path can be seen,

while to the east, Graham and Doubletop dominate the view, with the Big Indian ridge and the Burroughs Range beyond, and even some far-off glimpses into New England.

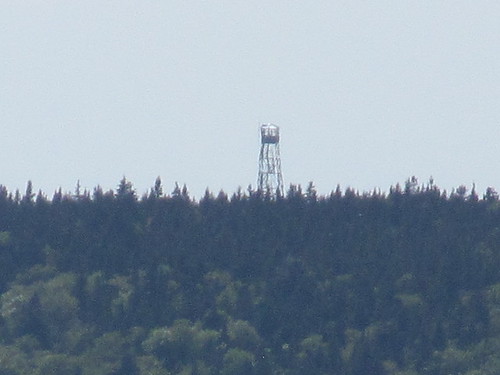

The television tower can just barely be seen on Graham if you click through to the big image, and ask for the original size from 'View all sizes.'

We can see down to the tiny lake that gives Balsam Lake Mountain its name:

and the enormous Pepacton reservoir, part of the New York City water supply system.

After coming back down from the tower and eating lunch, we were treated to a tour of the cabin, which features on the inside a display of all sorts of fire-fighting, search-and-rescue and land-conservation memorabilia.

We then headed back down the mountain. About three hundred yards beyond the DEC gate, an old woods road branches right. This road was part of the Jeep trail that was used to supply the television tower atop Graham. We take off on it. For an unmarked and unmaintained trail, it is extremely easy to follow. We were never once in doubt of our route.

On the way up, I noticed some frilly all-white wildflowers that I don't think I'd seen before. Anyone want to venture an identification? They don't seem to match anything in a couple of on-line identification guides that I consulted, but I know that these mountains play host to some very unusual species.

There are abundant Clintonia borealis in bloom, with butterflies busily at work around them.

The trail goes over some pointless ups and downs (the shoulders of the two Schoolhouse Mountains that I mentioned earlier, and then climbs in earnest to the summit of Graham. The summit ecosystem is different from any of the other Catskill peaks I've visited. There is virtually no balsam fir nor red spruce: I spotted only a handful of individuals, none bigger than a domestic Christmas tree. Instead, the mixed forest of the low elevations continues right to the top, with beech, ash, white birch, maple, sumac, and even hickory appearing. But the trees are stunted. None of them is above about fifteen feet tall.

At the summit, there stands a ruin with an intriguing past.

In 1961, Oneonta Video, Inc. raised funding to construct a microwave relay to start an early cable television system serving Oneonta, Sidney and Endicott, N.Y, bringing the signals by microwave relay from New York City. Part of the funding came from Instructional Television, a predecessor of PBS, to bring programming into the local schools. After multiple failed attempts, a power line was built along a bulldozed path to the top of the mountain, and a transmitter building and tower-mounted antennas erected. ("High TV tower nears completion." Mountain Top News 90:51 Margaretville, N.Y., June 21, 1962, p. 1)

Less than six months after its completion, the system was brought low by damage from a winter storm. Service technician Albert Bagnardi of Oneonta was sent up the mountain to repair it, making an attempt with a snowmobile on December 31, 1961, and again on snowshoes on January 2, 1962. He failed in both attempts to climb the mountain. Oneonta Video then hired helicopter pilot William DeJohn of Ilion to fly Bagnardi to the relay station to make the needed repairs, and the helicopter crashed atop the mountain in the treacherous winds of a Catskill January. The pair, unhurt, were stranded atop the mountain, but were able to take refuge in the transmitter shack and start its auxiliary generator. They were also able to use its equipment to radio Oneonta Video for help. They had neither extra food nor snowshoes, but could melt snow for drinking water on the hot generator engine, and could amuse themselves by watching television on the monitor in the shack - Bagnardi, while awaiting rescue, had succeded in repairing the microwave equpment. (Dobinsky, Pete. "Pair survive copter crash, await rescue." The Press, Binghamton N.Y., January 4, 1963, p. 3)

The pair were rescued on the evening of January 4 by a team of six rangers and policemen in a Sno-Cat driven by Frank Sherwood. They were brought down the mountain through a 4-5 foot snowpack, treated to a big meal at the Inn Between in Margaretville (still a going concern), and sent home for a much-needed rest. ("Cat that did the job." The Star 72:167, Oneonta, NY, January 5, 1963, p. 1)

I don't have any information about when the tower finally was taken out of service (and the dilapidated steelwork removed for safety), but if it lasted into the 1970's, it was surely irrelevant after Westar 1 launched in 1974 and RCA Satcom 1 in 1975. Those spacecraft provided video distribution for the major networks and a dozen or so new ones with names like Home Box Office and Entertainment and Sports Programming Network. Immediately, the old microwave video links were cost-prohibitive to maintain, and they have all fallen into disrepair. AT&T's microwave network hung on for a few more years, but eventually shut down with the breakup of the company in 1984.

What remains on Graham Mountain is a ruin, and Catherine was unimpressed.

The now-empty equipment racks have been yanked out, and are simply fallen in the dirt outside the shack.

The door of the shack is gone, and the roof has collapsed, leaving debris inside exposed to the elements.

Electrical conduit and wiring are torn off the walls, and the walls themselves have been torn apart in spots.

The drums of the station's fuel dump are rusting and overgrown with saplings.

Among the wreckage, Mourning Cloak butterflies (Nymphalis antiopa) flit about unconcernedly.

The area around the station, which had been clearcut, is now growing up to trees, and the view is largely obstructed. (I hear that there's still a good view to be had by climbing the station structure, but did not care to chance my weight on that crumbling hulk.) There's still a sight line to the west that sees Balsam Lake Mountain, and the camera, zoomed in as far as it will go, or a pair of binoculars, can pick out the fire tower.

By now, Catherine had grown quite impatient with all Kevin's photography, so we set up the tripod to give "two thumbs up" for the summit,

and started back down the trail. This time, we noticed a fuel drum set beside the trail in place of a cairn, and a side trail to an overlook. The overlook looks east down where the power line had been. (Even with a bulldozer, I'm amazed they managed to string the line up that cliff!) It has a nicely framed view of the Big Indian ridge.

On the way back down, it was Catherine who lallygagged for photography, finally getting one of the many amphibians that hopped out of the trail at our approach to model for the camera.

It was a tired pair of hikers who got back in the car, picked up a pizza in Arkville, and drove home up the East Branch and down the Schoharie valley. At sunset, we ran into an incredibly dense swarm of moths that sounded like a rainstorm against the windshield. The front of my car now looks furry with squashed bugs. I need to get it in for a wash soon!

Lesson learnt: Don't inflict 10 miles and 2500 feet elevation gain on a kid who hasn't been hiking in almost a year. Catherine's a trouper, though; few words of complaint and she soldiered on through the whole trip. Maybe sometime next week she'll decide that she had fun.

No comments:

Post a Comment