On Sunday, September 6, Cathy and I decided to go hiking again -

this time to Eagle and Big Indian Mountains in the Catskills.

She was

particularly eager to do Eagle because for her it was

the one that got away

and we decided that if all went well, we might be up to a second

peak. Big Indian is one mountain over, and you've done 2/3 of the

work of climbing it once you're on the approach trail!

We agreed to meet at 8am, Musician Standard Time (There isn't a

musician who's ever on time for an early morning appointment), got

rolling in good order and were on trail about 10:15.

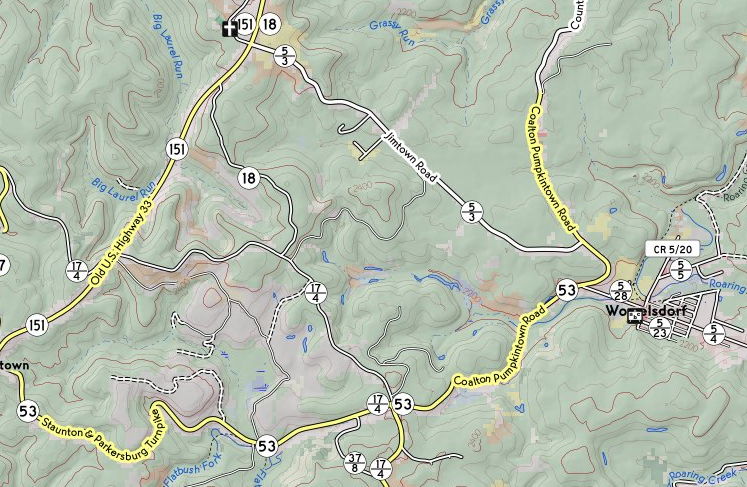

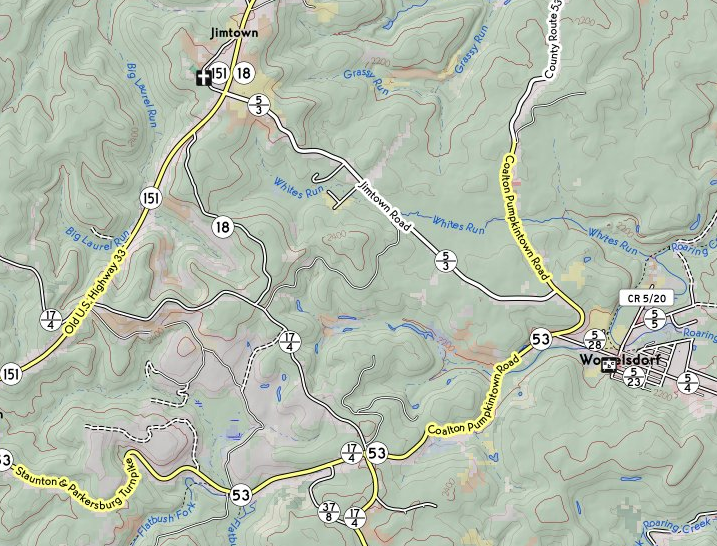

We headed for the trailhead at Seager, a settlement named for George

Seager, a settler who homesteaded there in 1800. The access road,

Dry Brook Road, winds up a picturesque gorge and passes three

covered bridges on the way in.

There were only two other cars at the trailhead,

bearing decals like

"Winter

35'er" and

"Long Path

End-to-End," so we knew we were in the company of some pretty

awesome hikers. We exchanged pleasantries and started up the couple

of miles of trail that cross Furlow, one of the estates of Gilded

Age robber

baron Jay

Gould, which still belongs to his descendants. The descendants

have graciously given hikers permission to access the trail (as well

as one or two other blazed trails that cross their land

elsewhere). The rest of the large estate is to be considered

strictly off limits.

The trail, an old carriage road, runs along the bank of Dry Brook,

with numerous fords of tributaries and traverses of washouts, some

of which have pretty sketchy footing.

It's a pretty easy stretch of

trail otherwise. It passes a lovely pool with a waterfall, which

would have tempted us to swim were it not for the fact that it was a

fairly chilly morning and there were obvious signs forbidding

trespassing. (Always respect the landowner!)

It's a pretty easy stretch of

trail otherwise. It passes a lovely pool with a waterfall, which

would have tempted us to swim were it not for the fact that it was a

fairly chilly morning and there were obvious signs forbidding

trespassing. (Always respect the landowner!)

Incidentally, Dry Brook is anything but dry! The origin of its name

is unclear. One speculation is that it was named "Drie Broek" by the

Dutch because it is the third large stream above the Forks of the

Delaware. That sounds a but odd to me: "Derde Kill," or "Derde

Beek," would seem more likely as a name. But I've not heard a more

likely explanation!

In any case, the trail comes to a place where it joins a private

road. It follows the road across the very wet Dry Brook at a

ford. Even in high summer, an SUV must drive through flowing water

there. I'm sure it's completely impassable in snowmelt! Again, the

footing was a bit sketchy, but we managed to cross dryshod.

It was there that we ran into our second party of the day. They

obviously belonged to a different subculture from ours.

“Are you guys heading to Camp 13?”(Never heard of it...)

“No, we're looking for where the trail up to Big Indian leaves the

road. We want to make sure we don't miss it.”

“You need to ask that tall guy in the red cap. He's a real

hiker and knows all the trails.”

Red-capped gentleman: “Oh, you mean up to the ridge? That

trail goes straight up, you know!”

“We'd heard there were a few spots of scrambles.”

“So, are you guys backpacking?”

“No, just here for the day.”

“Daytripping? All the way up there?” He shook his

head. “Good luck!”

We decided not to tell him that we were planning to attack two

mountains. We pretty quickly spotted the trail sign - the turnoff

is not nearly as obscure as others' trip reports had led us to

believe, and continued down a wet trail, now following Shandaken

Brook, fording it back and forth a few times. to the beginning of

the state-owned wilderness and a lean-to.

Up to this point (about 2.5 miles [4 km] in), there's been only

about 400 feet (120 m) of elevation gain. The trail now begins to

climb in earnest, gaining about 900 feet (275 m) more in the next

mile (1.6 km) taking a steep path full of loose rock with

blackberries on one side and nettles on the other. We managed to

avoid taking any bad scratches or stings, although Cathy did take a

bit of a tumble off a rock that was both loose and slick with

algae. She bounced right back up, with the only damage being a

slightly wrenched thumb from a trekking pole strap. She's a trouper!

Once we made it to the col, and started along the ridge for Eagle

Mountain. The trail was level a lot of the time, interspersed with

scrambles up steep ledges. (Everywhere in the Catskills, there's a

scramble at about 3400 feet (anout 1 km) elevation, where a layer of

soft mudstone is overlaid by a layer of much harder conglomerate

rock.)

We negotiated the scrambles, Cathy with more grace than

Kevin, found the turnoff, and arrived at the summit, where I was

surprised to find a canister. I learnt from other hikers that it was

only a year old. We signed in, and had a chat with another party—

relative newcomers to the Catskills—who were backpacking the Pine

Hill-West Branch trail over Big Indian, Eagle, Haynes, Balsam and

Belle Ayre mountains.

I don't know the origin of the “Eagle Mountain”” name, but

once upon a time, the Catskills were known for having the birds. Herman

Melville wrote [Moby-Dick, chapter 96]:

[...]there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down

into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become

invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within

the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his

lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds

upon the plain, even though they soar.

I'll think of that as the reason for the name; it might be an

uplifting enough thought to keep me climbing!

While we were eating our own lunch, we were visited by a couple: an

old mountain-man and his mountain-woman. We learnt that she's

completed the Catskill Grid: climbing each of the 35 high peaks in

every month of the year, for a total of 420 ascents. (Not an

achievement that would appeal to me: I like to see new

places!) We wished them well, they wished us luck in finishing the

35, and we headed back for the col.

At the trail junction, we had a strategy conference. It was

mid-afternoon by now, and we had to decide: do we head down, or do

we press on for Big Indian Mountain? We decided that if we still

had enough natural light to take the ford by the private road, we

could hike the remaining couple of miles by headlamp if necessary,

and decided to go for it. (We are not immune to get-there-itis.)

The way up along the ridge to Big Indian was a little longer and

steeper than the one to Eagle, There was more loose rock, more

scrambling, and a few tilting slabs of rock where Cathy was

pleasantly surprised that the soles of her new shoes gripped (so no

need to find better holds). The slabs are obviously a problem in

winter—they were covered with scratches from climbers' crampons

trying to gain purchase.

Along the way, Cathy asked me about the “Big Indian” name. I was

able to tell her that Big Indian Mountain, Big Indian Hollow, and

the village called Big Indian were all named for an extremely tall

native, the subject of a local legend that I couldn't recall. I

looked it up after we got home. The legend appears to be one of the

ones invented out of whole cloth by 19th-century

developers to sell land in their villages.

Winnisook, so the story goes [Charles M. Skinner,

Myths & Legends of Our Own Land.

Philadelphia, Penna.: J.B. Lippincott, 1896, pp. 28-29], was a

seven-foot-tall Algonquin, who fell in love with a Huguenot girl

from the hollow, named Gertrude Molyneux. He asked for her hand, but

her father refused, and insisted she marry a white man, She

conceded, and was married to one Joseph Bundy, who proved to be an

abusive drunk. Believing that she would be happier among the

natives, she eloped with Winnisook. Her family's search for her was

in vain, unto one day Winnisook was sighted leading a cattle-raiding

party. The villagers gave pursuit, with Bundy leading the chase.

Bundy, crying that Winnisook had stolen not only his cattle but also

his wife, fired his rifle. The mortally wounded Winnisook crawled

into the hollow of a pine tree, where the farmers lost sight of

him. Gertrude later found him there, sitting bolt upright, but dead.

The villagers were fond of pointing out the tree, until the construction

of a railroad in the valley removed it. (The railroad itself did not

survive for very many years.)

Since Skinner's book, the story has grown in the telling. Mary Lou

Stapleton, once a shopkeeper in the valley, added the detail that

nobody had been able to extract Winnisook's body from the tree, and

it had grown about him. As she tells the story: ['TravelStorys':

“Catskill Mountain Scenic Byway - Legend of Winnisook”, available

on

SoundCloud],

when the railroad men felled the tree, the skeleton of the Big Indian

fell out, and they said, "well, we have the name of our town now.

It's called Big Indian."

She went on to say,

I used to do events at my store. I would do a little event called,

“Celebration of the Big Indian.” I would have vendors

and I would have drumming. It was the last time that we did it and

it was a lot of people there. I came home and I was just

exhausted. And at three o’clock in the morning I woke up and it was

like someone was calling me. I went back down to the store and I

circle there, and I actually saw a vision. I saw all very, very old

indians dancing in a circle. And they were calling me. So I went in

the circle and I danced for two hours, until 5 in the morning, and

I was with all these native people. And I came back home and I went

to bed. A few months after that, I was given my name, and it was

“Spirit Dancer.” That was pretty amazing… That was

pretty amazing.

Winnisook Lake, and the exclusive Winnisook Club, at the head of the

valley, are also named for the Big Indian.

Whatever the truth of the legends, Cathy and I pressed on, she

unaware of them, and I having forgotten them. When the trail leveled

out near the summit, we started searching for how best to get to the

true summit and the canister. The trip reports we'd read all said

that there was a well-trodden herd path that led from the trail to

the canister. We scouted for it, and found three herd paths leading

east from the trail. The first, and most promising-looking, petered

out after a few hundred feet, at a false summit perhaps a

quarter-mile north of the true one. The second, nearly as

well-trodden, scrambled a ledge and then disappeared.

The third herd path was the least auspicious of the three, but third

time was the charm! We were able to follow it, falling briefly back

on the compass when it occasionally vanished, all the way to the

summit clearing (with a leaf-shrouded hit at a view to the

southeast,) We signed in, took the obligatory selfie, but didn't

hang around. We were going to have to make tracks if we were to have

light for the trip out!

We rushed all the way back on the same trails that we used to get

in, moving so fast that we occasionally noticed ourselves getting

winded and sweaty - on descent! We made excellent time,

arriving back at the trailhead around 7:15, doing the five miles (8 km),

including 1700 feet (about 500 m) of occasionally steep, scrambly, slippery

descent, and many rock-hops over creeks, in about two-and-a-half

hours. Cathy hadn't lit her headlamp at all. My vision in dim light

isn't as good as hers, so I had used mine for the last half-mile or

so, with the Sun having disappeared behind the Dry Brook Ridge and

the trail running in the shadows of a deep pine forest.

Cathy's smart-watch showed us as having hiked 13 miles (21 km) on

the nose, with 2400 feet (730 m) of elevation gain. That's probably

her most strenuous Catskill day yet, and close to being mine! We

scored two new technically-trailless peaks for Cathy, and one new

one for me, bringing my tally to 29/35 + 4/4 in winter—just six

climbs to go to finish the 3500's! Alas, Doubletop is now closed to

me. The owners are allowing only hikers from six neighbouring

mostly-rural counties to climb it, and I don't live in any of the

six. Unless the situation changes,, I'll probably max out at

34/35. Scuttlebutt on the trail is that Doubletop will soon be

closed to hikers altogether—the latest generation of the family is

more protective of the land.